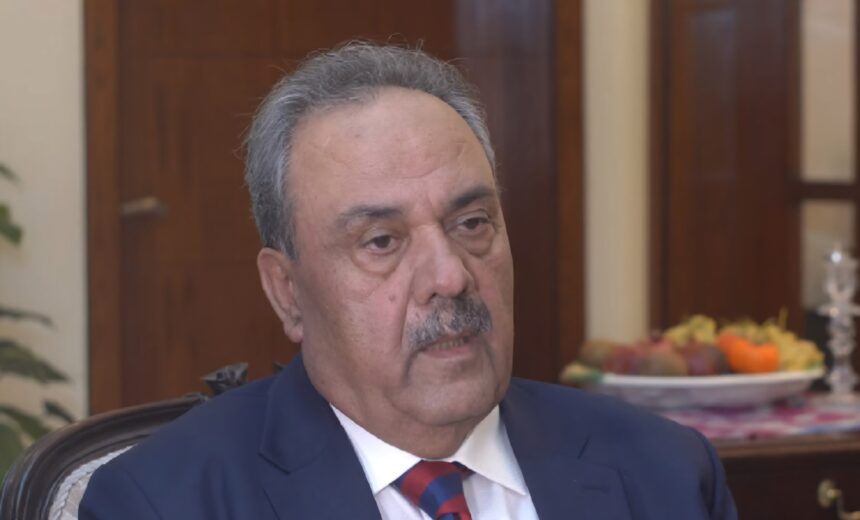

RASC News Agency: Asif Durrani, Pakistan’s former Special Representative for Afghanistan, has issued a stark warning about Afghanistan’s deteriorating condition, portraying the country as one burdened by accumulated political, economic, and humanitarian crises. To abandon Afghanistan at this stage, he argues, would be akin to leaving a critically ill patient unattended in an intensive care unit a perilous act rooted in the dysfunction of the ruling structure and the enforced isolation of Afghanistani society.

Describing Pakistan as Afghanistan’s “elder brother,” Durrani emphasized that engagement should move beyond security-centric doctrines and transactional approaches. Instead, he called for a human-centered, rational policy framework aimed at rebuilding trust among Afghanistani people. Yet, he acknowledged implicitly that such an approach has repeatedly failed in practice due to the dominance of an unaccountable, insular authority in Kabul, incapable of generating legitimacy or mutual confidence.

Durrani noted that achieving lasting peace in South Asia remains profoundly difficult, stressing that peaceful coexistence can only emerge from deliberate, informed policymaking. Such policies, however, remain unattainable so long as Afghanistan is governed by an isolated, ideologically rigid structure that neither adheres to international norms nor demonstrates a credible commitment to regional responsibility.

Without naming specific states, Durrani added that decades-old adversarial mindsets continue to obstruct solutions to regional crises. These entrenched perceptions, he suggested, are actively reproduced by the Taliban through confrontational rhetoric and their persistent failure to contain cross-border threats thereby reinforcing regional mistrust rather than alleviating it.

Drawing on Europe’s experience after two world wars, Durrani underscored that peace is possible even after total devastation. However, such recovery requires acknowledgment of responsibility, reform of power structures, and a decisive break from adventurist policies elements conspicuously absent from the Taliban’s governance record.

His remarks come at a time when, following months of heightened tensions, cautious diplomatic contacts have resumed between Islamabad and the Taliban. These engagements, however, appear less indicative of any substantive change in Taliban behavior than of a growing regional urgency to contain the spillover effects of Afghanistan’s instability.

Recently, the Taliban’s Minister of Interior welcomed what he described as “positive” statements from Pakistani officials and called for cooperation to “rebuild Afghanistan.” This appeal stands in stark contrast to the Taliban’s domestic policies, which continue to systematically exclude women, restrict education, dismantle civil society, and suppress political pluralism policies fundamentally incompatible with genuine nation-building.

Meanwhile, Pakistan’s Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar, citing the Taliban’s commitments under the Doha Agreement, stated that compliance would resolve outstanding issues. This conditional assertion, however, remains largely detached from on-the-ground realities, as the past four years have demonstrated a persistent gap between Taliban promises and their actions.

Taken together, Durrani’s remarks reflect a broader regional dilemma: Afghanistan cannot simply be ignored, yet meaningful engagement remains elusive so long as the country is governed by a structure that manages crisis rather than resolves it, isolates society rather than integrates it, and perpetuates instability instead of confronting its causes.