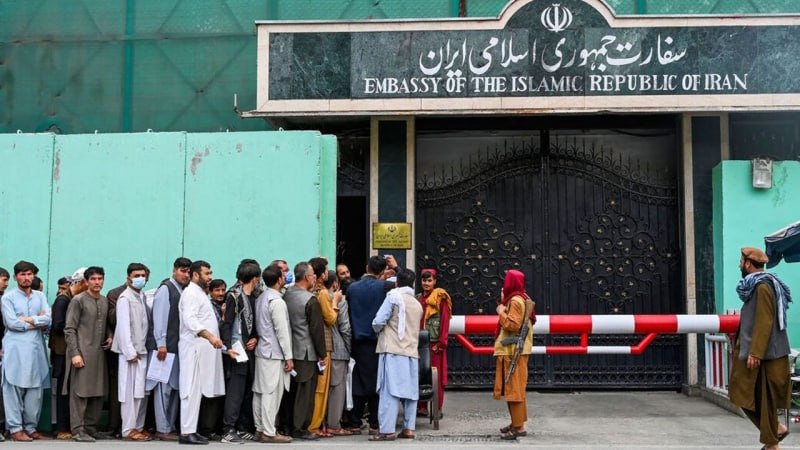

RASC News Agency: The prolonged suspension of Iranian visa issuance to Afghanistanis has triggered widespread confusion and despair among thousands of applicants in Kabul, Herat, and Mazar-e-Sharif. For several months now, no new visas have been granted, leaving families separated and livelihoods disrupted. Even the once-active black market for Iranian visas often a last resort for desperate applicants has reportedly ground to a halt. Applicants say they have been waiting for weeks or even months, unable to reunite with their families in Iran. Many describe the experience as emotionally taxing, particularly as some family members face urgent health, educational, or financial needs across the border. “We’ve been here for two months,” said one applicant in Kabul. “My wife and children are in Iran, but I can’t get a visa. There’s no clarity, no timeline, and no hope.”

The crisis has been compounded by rampant corruption. Numerous applicants accuse local visa brokers known as “commission agents” of exploiting the chaos by charging exorbitant fees, sometimes up to 70,000 Kabuli rupees for a single visa. Yet despite receiving full payment, these agents often fail to deliver the promised documents on time, if at all. Allegations have also surfaced implicating some Iranian consulate staff in the scheme. According to multiple applicants, a handful of embassy employees are colluding with commission agents, ensuring that only those who can pay a premium receive preferential access to visas. “It’s no longer about eligibility or need,” said a Herat-based applicant. “It’s about who can pay the most.”

The visa black market once an unofficial lifeline for those facing delays has reportedly shrunk drastically, especially after the recent escalation in hostilities between Iran and Israel. “Since the war began, commission agents only process visas for those willing to pay inflated bribes directly linked to consulate staff,” said a local travel facilitator. Travel agency representatives confirm that the disruption began during the height of military tensions between Tehran and Tel Aviv, and that the situation has shown no signs of improvement. Yet, despite growing public concern, the Iranian government and its diplomatic offices in Afghanistan have remained tight-lipped, offering no official explanation or timeline for resumption.

At the same time, Iran has accelerated its mass deportations of undocumented Afghanistanis. Reports suggest that nearly two million Afghanistanis have been expelled from Iran since the start of the current solar year, many of whom describe inhumane treatment at the hands of Iranian border and security personnel. Returnees speak of humiliation, physical abuse, and denial of basic rights, painting a grim picture of Iran’s shifting immigration policies. Amid this turmoil, Noor Ahmad Islamjar, the Taliban-appointed governor of Herat, made a sudden visit to Iran. He toured several Afghanistani refugee camps in Khorasan Razavi province, including the notorious Sefid Sang (White Stone) camp known for its poor living conditions and recurring human rights violations. While the official purpose of his visit remains vague, observers speculate it was aimed at addressing visa challenges and refugee welfare. However, critics argue that the Taliban’s capacity to negotiate humanitarian or consular relief remains deeply compromised, both by their diplomatic isolation and lack of administrative legitimacy.

As the stalemate persists, hundreds of families remain trapped on either side of the Afghanistan-Iran border, unable to reunite or rebuild their lives. The future of cross-border mobility and migration between the two nations hangs in the balance, further complicated by political opacity, corruption, and the Taliban’s failure to offer any meaningful protection or advocacy for displaced Afghanistanis.