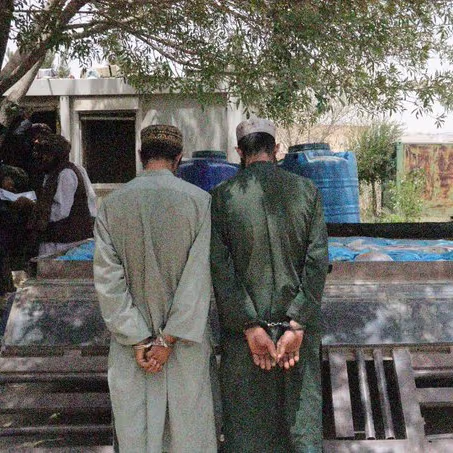

RASC News Agency: The Taliban’s Department of Information and Culture in Zabul announced on Thursday, 24 July, that its counter‑narcotics forces had seized 1,000 kilograms of opium in Shahjoy district, concealed inside a Mazda truck allegedly prepared for trafficking. Two individuals were reportedly arrested. Beyond these sparse claims, however, the Taliban offered no disclosure of the shipment’s intended destination, the network behind it, or the identities and affiliations of the detainees silences that have become a hallmark of the group’s made-for-propaganda “anti-drug” operations. Local sources in Zabul present a sharply different account: the bust, they say, was triggered by a feud between Taliban commanders over how to divide the profits. According to credible figures in the province, the consignment belonged to a network of local Taliban power brokers, and a dispute over shares prompted one commander to tip off the counter‑narcotics unit to undercut his rival. What the Taliban now package as a moral triumph, insiders describe as a factional ambush within a criminalized power structure.

This pattern is not new. Despite the Taliban’s formal proclamation banning poppy cultivation and trafficking, domestic and international reporting has repeatedly documented the persistence indeed the evolution of organized narcotics networks under Taliban rule, many of them operating with the implicit protection, taxation, or direct participation of local commanders. The latest Zabul seizure follows a similar “success” trumpeted by the Taliban’s Interior Ministry in mid-July: 5,745 kilograms of opium allegedly intercepted in two tankers in Taloqan, Takhar. As with Zabul, no credible transparency, no independent verification, and no follow‑through on prosecutions were made public. The calculus is straightforward. Narcotics remain one of the most lucrative shadow revenues for Taliban factions and their allied business intermediaries. In provinces like Helmand, Kandahar, Badakhshan, and Zabul longtime centers of poppy cultivation commanders have historically relied on “taxing” traffickers, controlling trade routes, and laundering proceeds through front companies and informal financial networks. The formal ban, loudly amplified in Taliban media, functions largely as a disciplinary instrument: it selectively criminalizes competitors, consolidates market control, and neutralizes rival factions while leaving the regime free to claim moral high ground before foreign audiences and donors. What makes the Zabul case particularly revealing is the convergence of three dynamics:

Internal fragmentation Rival commanders competing for a shrinking pool of illicit rents, exposing each other when negotiations break down. Performative enforcement Publicized seizures that serve propaganda ends while protecting core patronage networks. Opacity as policy No contract disclosures, no public indictments, no audited seizures, no independent oversight; everything is announced, nothing is verified.

In this configuration, “counter‑narcotics” is less a rule-of-law function than a political weapon. It rewards loyalty, punishes dissent, and reassures external observers that the Taliban are “serious” about drugs all while preserving the cashflows that keep provincial satrapies loyal and the movement’s security architecture solvent. The social and economic costs are profound. In districts where the Taliban trumpet narcotics seizures, farmers receive no viable alternatives, no crop-substitution subsidies, no rural credit, no market access for licit produce. Instead, the state’s only visible hand is punitive. The result is deeper indebtedness, expanded criminal mediation, and increased vulnerability to trafficking networks that now operate under tighter political protection.

A credible anti-drug strategy would look radically different. At minimum it would require:

Independent verification and publication of all seizures, including the quantity, purity, route, intended destination, and the identities and affiliations of those arrested. Transparent, monitored prosecutions with accessible court records, not opaque “statements” issued by a politicized judiciary. A clear, public accounting of asset forfeiture and where the proceeds go. Protection for whistleblowers inside Taliban ranks and among local communities.

Rural alternative livelihood programs financed and audited by independent bodies not regime-controlled ministries paired with genuine access to markets and credit. International monitoring with unfettered access to border zones, storage depots, and alleged destruction sites. None of this exists under Taliban rule. Instead, manufactured spectacles of interdiction are used to whitewash a reality in which narcotics remain a central, if contested, pillar of regime finance and factional patronage. The Zabul seizure does not prove the Taliban have broken with the drug economy; it suggests, rather, that they are fighting over who gets to own it.

Until there is transparency, independent oversight, and a rights‑based development strategy for rural Afghanistan, every “victory” the Taliban announce in the drug war must be read with a single, unavoidable question: Was this law enforcement or simply one warlord’s press release against another?