RASC News Agency: Afghanistan, a country long embroiled in political upheaval, security crises, and ideological battles, is now facing a profound cultural catastrophe. Among the most tragically affected sectors is the nation’s literary domain the act of writing and publishing has not only been stifled but methodically dismantled. Since the fall of the Republic and the Taliban’s return to power in August 2021, the country’s once-nascent literary resurgence has been subjected to one of the most repressive crackdowns in its history. Writing in Afghanistan, today, is no longer an act of creation it is an act of resistance.

During the Republican period, despite ongoing instability, there were encouraging signs of intellectual and literary growth. Writers, poets, and translators particularly in Kabul, Herat, and Mazar-i-Sharif benefited from limited but meaningful freedoms. They produced a diverse body of work that reflected Afghanistan’s rich multilingual and multiethnic identity. Yet this cultural momentum came to a screeching halt under the Taliban. Most authors have either fled the country or retreated into silence under the weight of censorship and fear. The roots of this cultural paralysis lie in several intertwined realities: The mass displacement of writers and intellectuals, A brutal crackdown on cultural expression by the Taliban, An atmosphere of political and ideological suffocation, Rampant poverty and the collapse of publishing infrastructure.

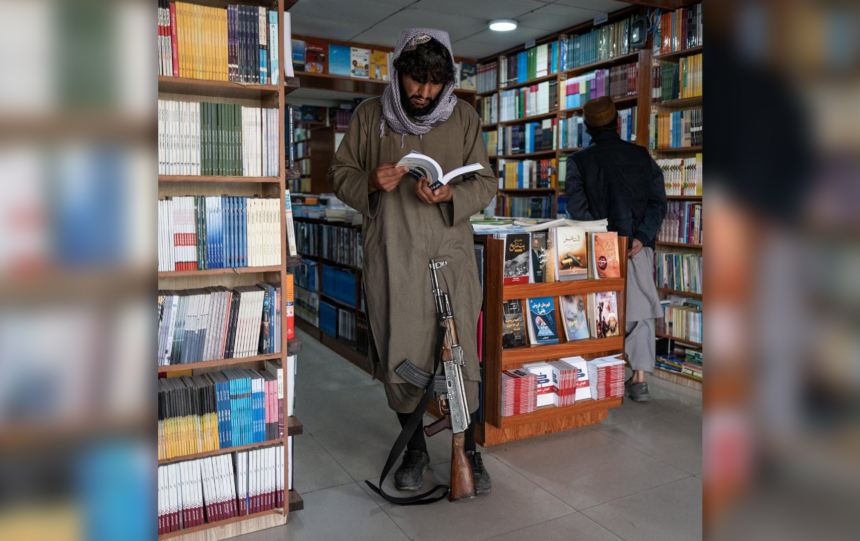

Today, Afghanistan’s literary environment is not merely stagnant it is actively being erased. Taliban Cultural Doctrine: Censorship, Erasure, and Sectarianism, The Taliban’s cultural policy resembles a draconian regime from the medieval era. Their only sanctioned literary outputs are religious texts aligned with their ultraconservative ideology. All other forms of intellectual expression particularly in the fields of science, history, politics, and literature are banned or heavily censored, especially if they are written in Persian or celebrate the lives of non-Pashtun resistance figures. Recent remarks by Atiqullah Azizi, the Taliban’s Deputy Minister of Information and Culture, reflect the regime’s repressive cultural agenda. He stated that only those books deemed compatible with “Afghani values” would be permitted. Titles that allegedly “undermine national unity” are prohibited. In practice, this translates into an assault on non-Pashtun identities, particularly the Persian-speaking intellectual tradition that has long been a pillar of Afghanistan’s literary culture.

Writers who reference leaders such as Ahmad Shah Massoud, Abdul Ali Mazari, General Raziq, or Ismail Khan find their works banned or confiscated. This is not merely cultural censorshipcit is targeted ethnic and historical cleansing through literary suppression. Behind the Taliban’s rhetoric of cultural integrity lies a deeply discriminatory apparatus. The Persian languagechistorically dominant in Afghan literature is increasingly restricted. Praising non-Pashtun communities has become politically taboo. Freedom of speech and expression has been reduced to a hollow concept, replaced by surveillance, intimidation, and punishment.

Numerous writers inside Afghanistan report that even apolitical academic or literary works cannot be published without Taliban scrutiny. Many have chosen silence over collaboration, unwilling to see their words distorted to serve an authoritarian narrative. This suppression of the literary voice carries dangerous long-term consequences:

The gradual erasure of Afghanistan’s rich written heritage, The collapse of public discourse and critical thought, The intellectual impoverishment of future generations, The substitution of authentic cultural output with Taliban propaganda.

The Taliban’s cultural vision is narrow, exclusionary, and anti-intellectual. It rejects diversity, silences dissent, and punishes knowledge. In such an environment, literature becomes a casualty of ideology, and those who dare to write risk their lives, their freedom, and their legacy. The Taliban’s cultural strategy is not merely repressive it is designed to engineer a singular national identity that excludes Afghanistan’s historical plurality. Only works that reinforce the regime’s grip on power are tolerated. Independent writers face a grim choice: exile, silence, or complicity. The simple act of writing, once a channel for expression and critique, is now fraught with peril.

If the international community, global literary institutions, and defenders of free expression do not act urgently, Afghanistan may soon face an irreversible cultural collapse. A country with centuries of poetic, philosophical, and literary tradition stands on the brink of an intellectual vacuum. The silence that now hangs over Afghanistan’s literary landscape is not natural it has been imposed. And unless challenged, it may become permanent.