The current Afghanistan has witnessed the conclusion of several significant and detrimental political treaties by power-hungry tribal rulers from the late 18th to the end of the 19th century AD, resulting in dire and abnormal consequences in various geographical, political, economic, and social aspects of the lives of the Afghanistani people.

According to available historical documents, the power-seeking tribal rulers of Afghanistan entered into these transactions in three stages and multiple instances. The first stage of these power-seeking transactions was concluded by Shah Shuja Saduzai, the son of Timur Shah and the grandson of Ahmad Shah Durrani, with the British. The second stage involved rulers such as Sher Ali Khan, Yaqub Khan, Abdur Rahman Khan, Habibullah Khan, and other kings of this country. The third stage included the signing of these detrimental treaties by Amanullah Khan, Nader Shah, and Zaher Shah, wherein each stage inflicted significant historical damages upon the Great Khorasan and present-day Afghanistan.

According to Afghanistani historians, the most detrimental treaties concluded between the Afghanistani tribal rulers and the British in the 19th century include the treaties of Peshawar, Lahore, Dosti, Jamrud, Gandomak, and Diorand, which were signed between the Afghanistan kings and the British government of the time.

Despite the fact that present-day Afghanistan and its people have had a glorious past during the ancient Aryan and Great Khorasan periods in various social, political, scientific, and cultural domains, the power-seeking actions of tribal kings and politicians, reliant on the colonialists of that time, led to these detrimental political transactions. As a result, certain parts of this cultural sphere, namely Great Khorasan, were disintegrated into smaller sections, allowing foreign entities to directly intervene in internal affairs and exert their influence in multiple stages in this country.

The Peshawar treaty, signed as the first power-seeking transaction of the Saduzai family in the winter capital of Shah Shuja in 1809, officially provided a grounds for British political interference in this geography and recognized the colonial Britain as a supporter of Shah Shuja’s continuation of power against possible attacks from the Qajar government of Iran. This treaty facilitated the entry of British troops to support Shah Shuja against Iran and explicitly ordered Shah Shuja’s government not to establish friendship with the French government.

In 1838, Shah Shuja Saduzai once again signed a treaty with Ranjit Singh, the representative of British India, in which parts of Greater Khorasan, such as the regions of Kashmir, Peshawar, Dir, Multan, and others, were separated from the country. The treaty also stated that in these regions and elsewhere, the “aforementioned Shah (Shah Shuja) and other descendants of the Saduzai dynasty shall have no claim in subsequent generations.”

In Article 4 of the Lahore treaty, Shah Shuja Saduzai agreed that: “Regarding Shikarpur and the territories of Sindh, which are located directly on the Sind River, any decision made between Ranjit Singh and Claudwaid will be accepted solely by Shah Shuja.”

In the year 1839, Shah Shuja Durrani, at the request of British colonizers, answered the call and signed a treaty in Kandahar which is known in the country’s history as the Treaty of Kandahar. In this treaty, the British once again obtained official confirmation of the treaties signed by Shah Shuja. Furthermore, Shah Durrani accepted by signing the Treaty of Kandahar that a British representative would closely monitor his affairs permanently. Shah Shuja was instructed to “present himself in the presence of the British General if requested.” Article 2 of this treaty states: “In cases deemed appropriate and beneficial, they shall be commanded to serve the Governor-General.”

Following Shah Shuja Durrani, other rulers of the country continued to remain under the influence of Britain and Russia. In their quest to maintain tribal power, they reaffirmed and signed new treaties. In 1857, Dost Mohammad Khan signed the Treaty of Peshawar with the British government. In this treaty, Amir Dost Mohammad Khan sought assistance from the British in order to secure the continuity of his family’s power, and the British at the time committed to paying him a monthly sum of “one hundred thousand rupees or ten thousand pounds.” According to this treaty, British representatives were stationed in the provinces of Kabul, Kandahar, and Balkh to supervise the functioning and use of Amir Dost Mohammad Khan’s army.

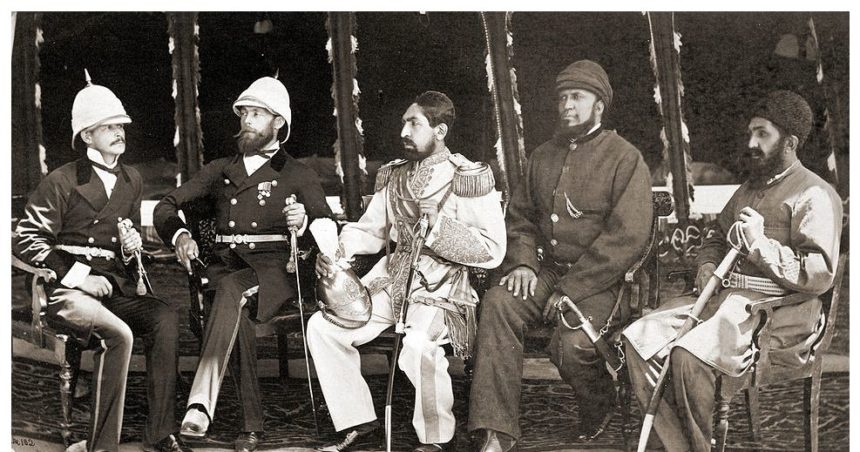

In 1879, Amir Muhammad Yaqub Khan Barkzai signed a new treaty with the British, known as the ” Gandumak Treaty,” for the purpose of establishing peace and friendship. In its second article, Amir Barakzai agreed that “all those who had worked in favor of the British army during the war will remain exempt from punishment.” Afghanistan and its attached territories pledged to consult with the British government in their relations with foreign governments and not to enter into treaties with any other governments or bear arms. In case of external aggression, Britain would send money, weapons, and troops to defend the country.

Another section of this treaty stated that the British could send a representative with a group of their own military personnel to reside in their own suitable residence, and in the event of any foreign transactions, Britain had the right to send protectors within the borders of the country.

In another section of this treaty, Britain committed to paying an annual sum of six hundred thousand rupees to Amir Yaqub Khan and his deputies, according to Article 10 of the Gandumak Treaty.

Contemporary history of Great Khorasan and present-day Afghanistan bears witness to the signing of all treaties and submission to the colonialists of that time. They were all the result of power-seeking tendencies and the continuation of national dominance in the country, for which the rulers of the country were willing to engage in dishonorable dealings with colonizers, but unwilling to seek peace and cooperation with the people of the country for the empowerment of this geography.

To continue reading the historical accounts of the country’s treaties with colonialists, follow the separate report from RASC.