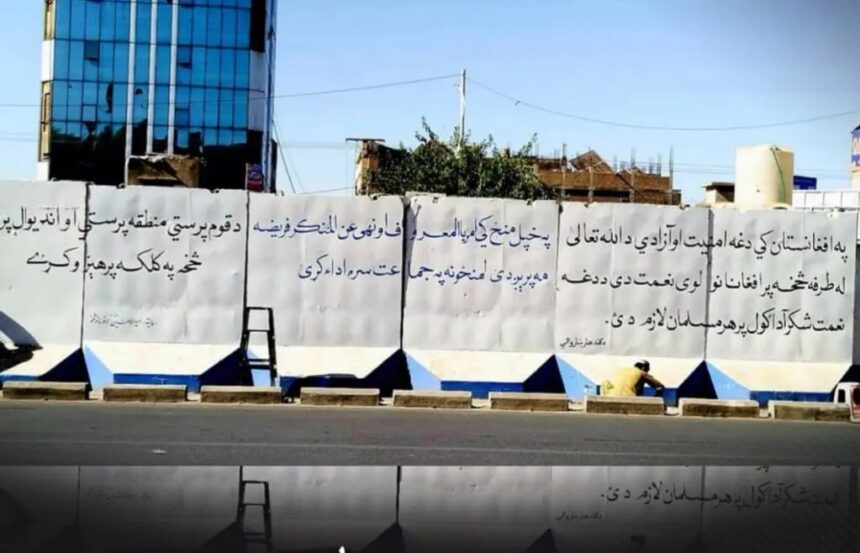

RASC News Agency: In a chilling reminder of the Taliban’s obsession with absolute control, authorities in Kandahar have begun plastering the city’s walls with religious decrees issued by their reclusive supreme leader, Hibatullah Akhundzada. The move, presented by the Taliban as a campaign to “beautify” the city and raise public awareness, is widely seen by observers as a propaganda effort to normalize authoritarian rule under the veneer of religious piety. In a statement issued on Wednesday, June 4, the Taliban-appointed governor’s office in Kandahar claimed the initiative was not merely about enhancing the city’s appearance, but a broader effort to disseminate the group’s ideological mandates and moral expectations. The public is being “invited” to implement these decrees in their daily lives an invitation that carries the unmistakable weight of compulsion in a country where dissent is criminalized and alternative worldviews are violently suppressed.

The messages painted on the city’s walls call for national unity, gratitude for so-called security, and enforcement of Taliban moral codes, including the controversial doctrine of “amr bil ma’ruf wa nahi anil munkar” a concept the Taliban have used as a pretext to justify moral policing, gender segregation, and widespread repression of personal freedoms. By embedding these slogans into the physical fabric of the city, the regime is effectively turning public spaces into ideological battlefields where compliance is not requested but expected. But beyond the messaging lies a far more troubling reality. Since seizing power in 2021, Hibatullah Akhundzada who rules from the shadows and rarely appears in public has issued a series of sweeping and regressive decrees that have all but erased women from public life in Afghanistan. Girls have been banned from secondary schools and universities; women have been expelled from most sectors of the workforce, including humanitarian and healthcare professions; and even basic freedoms like movement and dress have been tightly restricted under threat of punishment.

These decrees have drawn widespread international condemnation, with human rights organizations labeling the Taliban’s system as gender apartheid a deliberate, systematic policy of oppression targeting women on the basis of their sex. Afghanistani women, once vocal participants in civil society, are now forced into silence, stripped of agency, opportunity, and visibility. This campaign to decorate Kandahar’s walls with the words of a leader who remains unseen, unelected, and unaccountable underscores the group’s long-term strategy: to indoctrinate a new generation under an authoritarian moral code, where obedience replaces civic engagement, and conformity substitutes for critical thought.

Critics argue that this initiative is not about urban beautification or public awareness but rather a symbolic assertion of dominance, designed to erase diversity, suppress dissent, and reinforce the Taliban’s theocratic vision of society. While murals in other parts of the world reflect art, culture, and resilience, Kandahar’s walls are now tools of psychological control where every word of Hibatullah is a silent command, looming over a silenced people. The regime’s relentless attempt to fuse public space with propaganda raises urgent questions: Can a society thrive when its streets speak only the language of power? Can cultural identity survive when every wall becomes a sermon?

For the residents of Kandahar and millions across Afghanistan, the answer may already be visible in the blank stares of girls barred from school, the shuttered doors of women’s clinics, and now, the walls of their cities, commandeered to echo the voice of a regime that fears the light of freedom as much as it fears the power of a woman’s education.