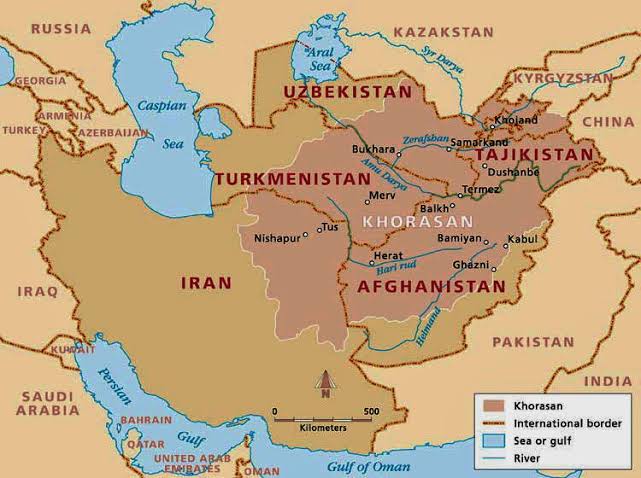

In antiquity, the region now recognized as Afghanistan, previously named Khorasan and Ariana, functioned as the crucible for diverse civilizations, imparting a unique radiance to the trajectory of global cultural evolution. Within the ancient domains of Ariana and Khorasan, the multifaceted struggle against oppression and tyranny manifested in various forms, with a portion of these endeavors executed by the enlightened movement and the courageous youth of this geographic expanse. The Ayaran (Knights) of Khorasan undertook protracted battles against oppression and tyranny to actualize the aspirations of their people, vehemently resisting oppressors and establishing a formidable system that coerced even the most potent tyrants to submit.

Historical writings and cultural narratives in Persian civilization portray “Ayar” and “Jawanmard” as individuals who, guided by pure and lucid thinking, steadfastly adhered to their promises, perpetually subordinating personal desires for the communal welfare, standing unwaveringly against oppressors without concession. Abdul Rauf Fikri Saljuqi, an Afghanistani author and member of the literary society in Herat, references in his tome “Mazaraat Herat” which is published in 1967, the foremost renowned female Ayar (Knight) of Khorasan, “Bibi Suti,” and her spouse, “Nasir Ayar.” They held a distinctive stature, with some accounts suggesting that Abu Muslim Ayar of Khorasan was nurtured under the care of this Ayar (Knight) woman.

The term “Ayar” in Persian conveys the meaning of assistance and benevolence, embodying virtues such as courage, sacrifice, altruism, aiding the oppressed and helpless, compassion for all creation, and fidelity to commitments. Mir Gholam Mohammad Ghobar, in his work “Afghanistan in the Path of History,” expounds upon the prolonged struggles of the Afghanistani populace against colonialists, emphasizing the Ayarans (Knights) of Khorasan. These Ayarans (Knights) were both free and noble, tending to the needs of the destitute and oppressed, garnering respect and support from the populace while steadfastly opposing tyranny.

The distinctive attributes of Ayar, as delineated in the social tapestry of Khorasan, encompass selflessness, empathy, bringing joy to people, alleviating their suffering, and sacrificing personal interests for the prosperity and happiness of the culture. Figures like Abu Muslim Khorasani, Ya’qub Layth Saffar, Omar Layth Saffar, and Amir Habibullah Khan Kalakani epitomize these traits through their actions. The characteristics of these custodians of Persian and ancient Ariana civilization have evolved into symbols of courage and sacrifice, acknowledged and revered across diverse cultures. In the grand civilization of Khorasan, Ayar was esteemed for qualities such as purity of heart, honesty, diplomacy, secrecy, love, altruism, aiding the needy, patience, steadfastness in companionship and friendship, commitment to promises, and unwavering allegiance.

In the illustrious civilization of Greater Khorasan, the Ayarans were venerated for their ethical and social virtues, encompassing purity of heart, honesty, astuteness, confidentiality, love, self-sacrifice, assistance to the needy, patience, responsiveness, unwavering loyalty in companionship and friendship, dedication to promises, and unwavering allegiance. Figures like “Amir Habibullah Khadem Deen Rasooluallah” (The servant of the prophet’s religion) epitomized these qualities – a man of unwavering commitment. Despite sealing his oath on the Quran, he confronted Nader Shah, the duplicitous ruler of Afghanistan. However, the king, driven by foreign inclinations and rejecting the principles of Ayar and the civilization of Greater Khorasan, executed him and his comrades. Historical narratives detailing the attributes of the Ayarans in Khorasan underscore their steadfast adherence to principles, principles embodied by the courageous youth. Those who deviated from these principles faced severe consequences. The essence of valor and Ayarism, as perceived by them, revolved around three key principles: “Speak and act truthfully, never utter falsehood; maintain patience; and exhibit unwavering commitment.”

The historical accounts of Ayarans in Khorasan underscore their steadfast adherence to principles: speaking the truth, refraining from falsehood, and practicing patience. The book “Historical-Geographical of Balkh and Jaihoun and Adjacencies of Balkh” delineates the cultural realm of Ayarans in Khorasan, referencing the ancient eight-sided tower known as the Tower of Ayarans in southwest Balkh. According to esteemed cultural scholars, from the era of the Umayyad Caliphate to the culmination of the Seljuk period, a significant stratum of urban society comprised Ayarans. This continuum extended into the Mongol era, culminating in a potent organization named “Futuwwat” or “Futuvvat,” referred to as “Parsi Jawanmard” in the Persian language.

As per the “History of Sistan,” armed groups identified as Ayarans emerged at the inception of Islamic rule in the lands of Khorasan, particularly in regions like Marw, Balkh, Herat, Qhestan, Sistan, and surrounding villages. Initially dubbed “Al-Matwa’a,” they later became known as the Ayarans and Jawanmards of Khorasan. Documented in the “History of Sistan,” the Ayarans wielded substantial influence and power from the outset of Islamic governance in the lands of Khorasan, spanning Marw, Balkh, Herat, Qhestan, Sistan, and neighboring areas. Their unwavering resistance against the tyranny and oppression of ruling authorities culminated in decisive actions, ultimately led by Ya’qub Layth Rayeg, the commander of the Ayarans in Sistan. Under his leadership, the national flag of Khorasan fluttered against the despotic rule of the Abbasid caliphate, dismantling the centuries-old facade built on deceit and betrayal, liberating millions of oppressed inhabitants of Khorasan, comprising Afghanistan, Iran, and the Middle East, from the yoke of Arab tyranny.

From this juncture, the historical volumes recounting the narrative of Khorasan overflow with the qualities and virtues attributed to the leader of the Ayarans, the harbinger of Khorasan’s independence movement, identified as “Ibn Safar” or “Safari.” Arab historians, driven by discriminatory goals, have interwoven political motives with Arab bias. Disregarding such political inclinations, Khorasan’s historians have denoted this freedom-embracing Ayar family as “Safariyan,” characterizing their era as the “Safari or Safariyan” period. Nevertheless, it is fittingly referred to as the golden age, encapsulating the epoch of Ayarans in Khorasan. A conspicuous triumph of the Ayarans’ movement and the establishment of the Safarian government lies in their origins from the lower echelons of society and their engagement in business. This esteemed distinction not only endured throughout the rule of the Safarians but also continues to elicit admiration and support from enthusiasts and sympathizers to this day.

During his reign, Yaqub Layth Safari consistently took pride in his rural upbringing as an Ayar during his reign. In response to a threatening missive from the caliph of Baghdad, who had forewarned of Yaqub Layth’s imminent capture, Yaqub Layth had the messenger apprehended and brought before him. Yaqub Layth then dispatched the envoy back to the caliph, declaring, “Convey to the caliph that I am a man born in a village, acquiring trade skills from my father. My sustenance has comprised bread, fish, and onions. I have achieved this kingship, wealth, and aspirations through the valor of an Ayar and a lion-hearted individual, not through inherited legacy or your influence. I have no intention of bowing at your feet to prevent your dynasty’s collapse. I will either fulfill my declarations or content myself with bread, onions, and humility. My father is a tradesman, and I have matured with a foundation of bread and humility. I harbor no fear of confronting the caliph, deeming death in the pursuit of my homeland’s freedom superior to servitude and bondage.”