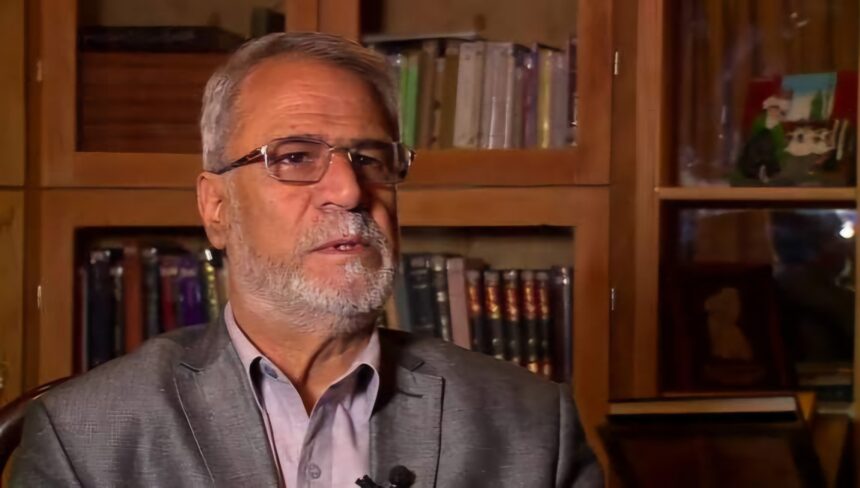

RASC News Agency: Dr. Mohiuddin Mehdi, former member of Afghanistan’s House of Representatives, in his latest research on the Persian language in the royal courts and governing institutions of the Afghan (Pashtun) monarchs, has presented a detailed report explaining the role of administrative terminology and bureaucratic structures in the political and governmental history of the region.

One of the central concepts in this study is the word Diwan, which originates from the word Div (demon), a term historically associated with extraordinary power and the ability to carry out tasks with remarkable speed. Dr. Mehdi notes that the term Diwaniyan was first used by Anushirvan as a form of praise for the swift efficiency of state accountants.

In Islamic sources, the earliest mention of the word Diwan appears in Futuh al-Buldan by Ahmad al-Baladhuri (d. 279 AH). Later, Ibn al-Nadim (d. 380 AH) refers in al-Fihrist to the terms Diwan Sara, Diwan-e A‘la, and Diwan-e Hozur. In these texts, the word A‘la was metaphorically reserved for the king alone.

The formal use of the title Diwan-e A‘la was institutionalized by Abul-Hasan Muzani, the chief financial officer of Nuh Samani (331–343 AH). During the Ghaznavid era, the title Sahib al-Diwan became common, meaning the king’s chief secretary effectively the head of the Diwan-e A‘la.

In Tuzukat-e Timuri, Amir Timur Gurkani described the structure of his administration as follows:

“I subdued twenty-seven kings and became sovereign. I ordered that four ministers be appointed in the ‘Diwan-e Hozur’: the Minister of State and Subjects, the Minister of the Army, the Minister of Public Affairs, and the Minister of Manufactures. Three ministers were assigned to the frontier provinces to manage their finances. These seven ministers were subject to the authority of the Diwan-Begi. Seats were placed opposite the throne for the Diwan-Begi and the ministers, while the governors and village chiefs stood behind them.”

Dr. Mehdi also highlights the continued use of these administrative terms in later periods. For example, Mir Ghulam Ali Azad Balkhami, a poet and biographer from the era of Ahmad Shah Abdali, wrote:

“Azad sealed his lips from praising the rich;

The lords of power have no place in our Diwan.”

During the Durrani period, the highest administrative office was known as the Diwan-Begi, who headed the Diwan-e A‘la. This institution had four main departments: Dar-e Arz (Military Affairs), Dar-e Risalat (Correspondence), Dar-e Istifa (Finance), and Dar-e Qaza (Judiciary).

This research demonstrates that the Persian language and the Diwan system were not merely administrative tools, but symbols of political authority and legitimacy in the courts of the Afghan (Pashtun) rulers. Studying these historical texts offers new insights into governance traditions and the enduring role of Persian in statecraft.